There is a book called Be our Guest: Perfecting the Art of Costumer Service that sums up why Walt Disney is one of my heroes in life. I was thrilled to find out just how much this book has to do with Game Design.

I was thrilled that two of my greatest passions in life (video games and Disney Parks) have so much more in common than meets the eye. After all, Disney Parks aren't magical, even though they may feel magical, they are a result of hard work, attention to detail, strategic planning...

So, happily, Disney Parks aren't that full of magic after all.

Factories of Experience

Disney Parks, much similar to video games, are built to craft experiences. As game designers, we create systems that enable experiences. Disney Parks are all the same at its very core, they are factories that create experiences.

It seems cold and emotionally empty, but if one were to look at a Disney Park from an objective perspective, it's no more than a carefully designed system that enables people to have meaningful experiences.

Crafting these systems is not easy at all, one must not only have attention to detail, one must obsess over it, everything counts, everything builds up to an experience, of course, sometimes one needs to learn how to let things go.

|

| Trash Bin Fantasyland - Magic Kingdom |

|

| Trash Bin Tomorrowland - Magic Kingdom |

One of the things I've always loved the most about Disney Parks are the trash cans. I was the type of child who would go marvel at the beautifully incorporated trash cans in Magic Kingdom, as an adult I could clearly see why, I mean, the trash cans in Tomorrowland are completely robotic... and they even talk! They definitely are masters of putting attention to every detail in their parks!

The following is a video of a talking trashcan in Tomorrowland:

Disney himself was a heavy smoker, but he never smoke in front of children because he didn't want to set a bad example. Attention to detail doesn't mean not being human or being perfect, it means knowing what to show to the public, how to show it and when to show it.

In game design, attention to detail is a must. In a game, everything must fit withing the system, everything must be placed in the right place to enable the players' experience. In almost every great game the attention to detail is part of the development process, it's not just about observing the game in its final stage, it's about observing what needs to be observed in every step of the way.

Let's say that we are making a game from scratch and we begin the process of laying out the mechanics, or grayboxing, no art, not sound, just mechanics. Obsessing over missing art or sounds details does not make sense at this stage of development, so the designers must focus in the naked mechanics. They need to tweak and iterate so that they are ready to enable the experience they want to provide and so on.

Disney Parks have underground tunnels which enable employers to move between sections without being seen if the visitors aren't meant to see them, so you wouldn't see a Fantasyland employee walking in Tomorrowland, thus not dressed accordingly to the customers' experience, these tunnels are part of the complex system of mechanics that enable a clean and magical user experience in Disney Parks.

Playtesting

There is a key process in Game Design called Playtesting, playtesting is the process in which players play the game and the designers observe. It is a difficult process because in most cases the Game Designer needs to sit quietly and watch the gamers tear apart the game. Either by winning to easily or not winning at all, by missing doors that should have been obvious or not knowing what to do. It's agony.

As designers, we know our games by heart. I can play almost every game that we are doing while looking somewhere else most of the time. I know what every sound means, and when to watch, I know where the buttons are, I know what's supposed to happen every second of gameplay. Which is why I would be a terrible game tester. Playtesting works because playtesters don't know the game, thus they are experiencing what a player should experience.

The other big challenge of the playtesting process is know which data is disposable and which signs should we listen to. Correcting something in a game has an associated cost, and depending on the advanced of the game development process, the cost may be very low, or very high. Understanding that there are some aspects of our game that need to change due to playtesting results is not easy, because it means throwing away our hard work to be replaced by down to earth mechanics.

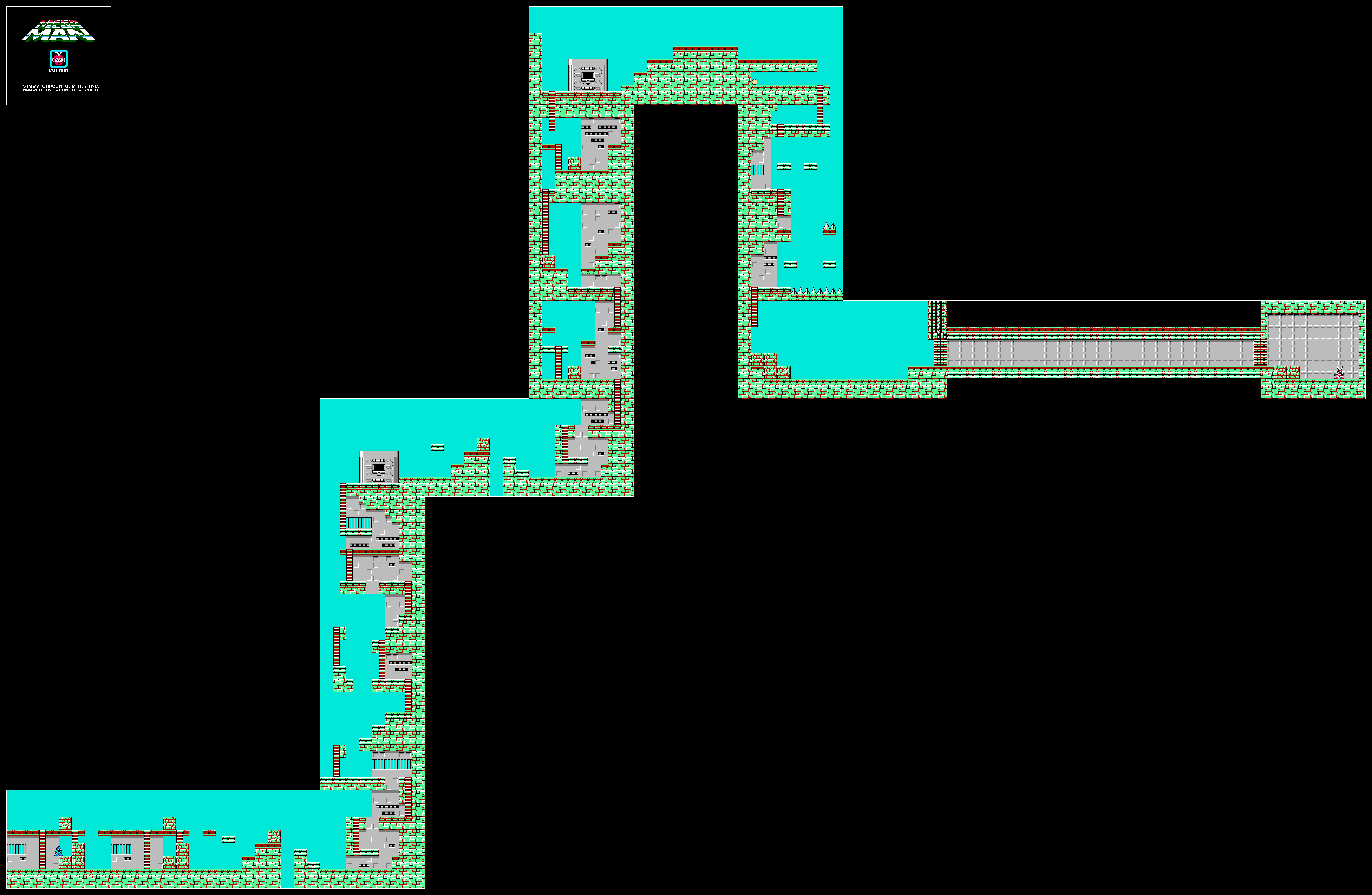

|

| Halo would be a top down strategy game if it weren't for playtesting |

If it weren't for playtesting, many great games wouldn't even exist. For instance Halo, the popular First Person Shooter, was initially conceived as a top down strategy game. It was after playtesting that the designers understood the true potential of their game and it turned slowly and through many iterations, into the FPS that we all know today.

Some Designers say that they are discovering their game, I truly believe this to mean that they are observing what players find engaging and what they don't, having the flexibility to change what needs to be changed, the speed to iterate as fast as possible and the bravery that involves throwing away their work when it needs to be thrown away.

This is another great thing that Walt Disney's design process of Disney Parks and Game Design have in common, quoting Be our Guest:

Walt would wear old clothes and a straw farmer’s hat and tour the park incognito. Dick Nunis, who was at the time a supervisor in Frontierland, remembers being tracked down by Walt during one of these visits.

Walt had ridden the Jungle Boat attraction and had timed the cruise. The boat’s operator had rushed the ride, which had ended in four and a half minutes instead of the full seven it should have taken.Dick and Walt took the ride together and discussed the proper timing. The boat pilots used stopwatches to learn the perfect speed. Weeks went by until one day Walt returned. He road the Jungle Boats four times with different pilots.In the end, he said nothing, just gave Dick a “Good show!” thumbs-up and continued on his way

Sounds familiar? Walt Disney used to playtest his rides! It's what must be done in Game Design, observing incognito while our players play and understanding what needs to be changed to enhance experience.

Video game is such a new field that even though there are some standarized and recommended practices, they don't work for every company, and each company works different and implements different processes. Sometimes we even take concepts from other industries, such as the film industry, and incorporate them without a second glance to the design process, whether they work or not.

I believe that we have a lot to learn from Disney's vision of his business, of finding economic success through high quality products resulting from processes that always have the customer in mind. That, at its core, smells of success.